Realms and Evaluator Shim Security

Agoric

October 23, 2019

Brian Warner, 24-Oct-2019

Summary: Two security bugs were found and fixed in the realms-shim library. A new, simpler evaluator-shim library is being developed, with a smaller attack surface. The realms-shim library is being retired in favor of evaluator-shim, and future security efforts will focus on this alternative library.

Introduction

On 04-Oct-2019 and 07-Oct-2019, two new security bugs were reported in the realms-shim repository. As before, the issues were quickly analyzed, and fixed by realms-shim-1.2.1, released 16-Oct-2019. All users of the Realms shim (and the SES library) should upgrade to this version.

This post describes the new bugs and the fixes. It then examines lessons from this incident and describes a new, smaller library named the evaluator-shim, upon which we will focus our security efforts in the future.

The realms-shim library will no longer receive security updates, and this post explains additional security bugs we discovered in the process of fixing the previous ones.

Bug One: Symbol.unscopables

As described in the previous post, the realms-shim package implements the Realms proposal, a standards-track enhancement to the core JavaScript language. The main feature of a new Realm is the evaluate() method, which provides a “safe two-argument indirect eval with options”. This eval is “safe” because it neither provides access to the caller’s lexical environment (as the standard “direct” eval would do), nor does it grant access to the platform global object and the various high-powered window, document, or require() properties on it (as a standard “indirect” eval would do). Instead, each evaluation takes place in a “compartment” which has its own separate global object, that contains none of the powerful platform globals.

The previous post described the “eight magic lines” at the core of the evaluator. These lines use a with statement around a block of code. Any name lookups inside that block that would normally reference global variables are instead routed to a Proxy object. The Proxy then allows the first eval reference to connect with the real evaluator (making it a “direct” evaluation), and all other references get connected to the per-Compartment global object (protecting the caller, and the internals of the shim itself).

In JavaScript, the target of a with block can have a property with the special key designated by Symbol.unscopables, and its value is used to exclude names from the with capture, allowing those lookups to pass outwards to the real global. To prevent this, the realms-shim proxy watches for lookups of Symbol.unscopables and prevents gets and sets of that key. (Note that the property name is not a string: it is a special type known as a “Symbol”, and that particular value is only reachable as a property of the Symbol global)

GitHub user @XmiliaH reported a sandbox breach that only occurred under the Microsoft Edge browser (version 44.17763.1.0). Apparently, the JavaScript engine in that browser has a bug that causes Symbol.unscopables to sometimes fail an equality test, bypassing the proxy’s exclusion logic. We confirmed that current versions of Safari, Firefox, Chrome, and Node.js do not behave the same way, and do not appear to be vulnerable.

We reported the bug privately to the Microsoft Security Response Center (as MSRC Case#54433). After a few days, they confirmed the presence of the bug, but decided it did not warrant a security disclosure process (nor a bug number, presumably because of the imminent switch to Chromium), and said we should feel free to present our findings publically.

We fixed the realms-shim bug as a side-effect of rewriting the proxy handler, in commit b19cecf. Instead of denying access to Symbol.unscopables specifically, the handler was rewritten to deny access to any symbol. This works around the Edge bug, and does not change the behavior on other engines.

Bug Two: Rewrite Transforms

The realms shim’s evaluate() method takes the code string to be executed as the first argument, and a set of “endowments” as the second. Endowments are a little like globals, in that they are present in the global lexical scope (and thus available everywhere within the code being evaluated), but they are not aliased to properties on the global object. The optional third argument is an options bag.

One of those options is named transforms, carrying a list of objects with rewrite methods, that modify the source string and the endowments. These are not yet well documented, but are used to apply things like Babel transformations. Our SwingSet platform uses this to enable the “wavy dot” (~.) notation in smart-contract code evaluated in a confined Vat.

Wrong-Realm Records

To implement transforms, the shim calls a function named applyTransforms() which must iterate through the provided rewrite methods and execute each one, giving it a “rewriterState” record that contains the old code string, and the old endowments. Each rewrite method returns a new state record with the new code string and the new endowments (or undefined, in which case the endowments are left unmodified). The code looks like this:

function applyTransforms(rewriterState, transforms) { // Clone before calling transforms. rewriterState = { /// <- parent-Realm Object! src: `${rewriterState.src}`, endowments: create( null, getOwnPropertyDescriptors(rewriterState.endowments) ) }; // Rewrite the source, threading through rewriter state as necessary. rewriterState = transforms.reduce( /// attacker-supplied .rewrite method gets parent-Realm rewriterState! (rs, transform) => (transform.rewrite ? transform.rewrite(rs) : rs), rewriterState ); ...

From an authority point of view, the rewrite methods are given access to the endowments. That’s ok. What isn’t ok is that the rewrite methods also got access to the rewriterState record, which was created inside applyTransforms(), which was implemented in the parent Realm, not the one where the evaluation was going to happen. As a result, the rewrite method got access to the parent Realm’s Object. When the parent Realm is the “Primal Realm” (i.e. the top-level browser or Node.js environment), that Object yields access to the real Object constructor, from which it can get the real Function constructor, and from there it’s only a short hop to access require() or document and fully compromise the application.

To mount this attack, the confined code creates its own child Realm, and then evaluates some dummy code inside it. That evaluate() call is given a { transforms: [...] } option bag, and one of the rewrite methods takes the record it is given and extracts the record’s .constructor from it. It then follows the chain up to the primal-realm Function constructor. From that it can evaluate code against the real global object, which has require() and full application authority.

The fix is to use a copy of applyTransforms() that was evaluated in the same Realm as the one that will ultimately get to evaluate the code being transformed. The original function is turned into a string, and that string is evaluated in the target Realm, to get a new copy of applyTransforms(). This new copy is used for any actual evaluation that involves rewriter transforms. As a result, the attacker’s rewrite() call gets a rewriterState that was built in the same Realm as the attacker, so it doesn’t give them any additional access.

Array concat and reduce

A day later, a related breach was submitted. The exploit code calls evaluate with a transforms option that isn’t a real Array: instead it’s an Array subclass that overrides the reduce method. It targets two functions. The first is the code that assembles a list of transformations by combining the attacker-supplied localTransforms with other internal transformation functions:

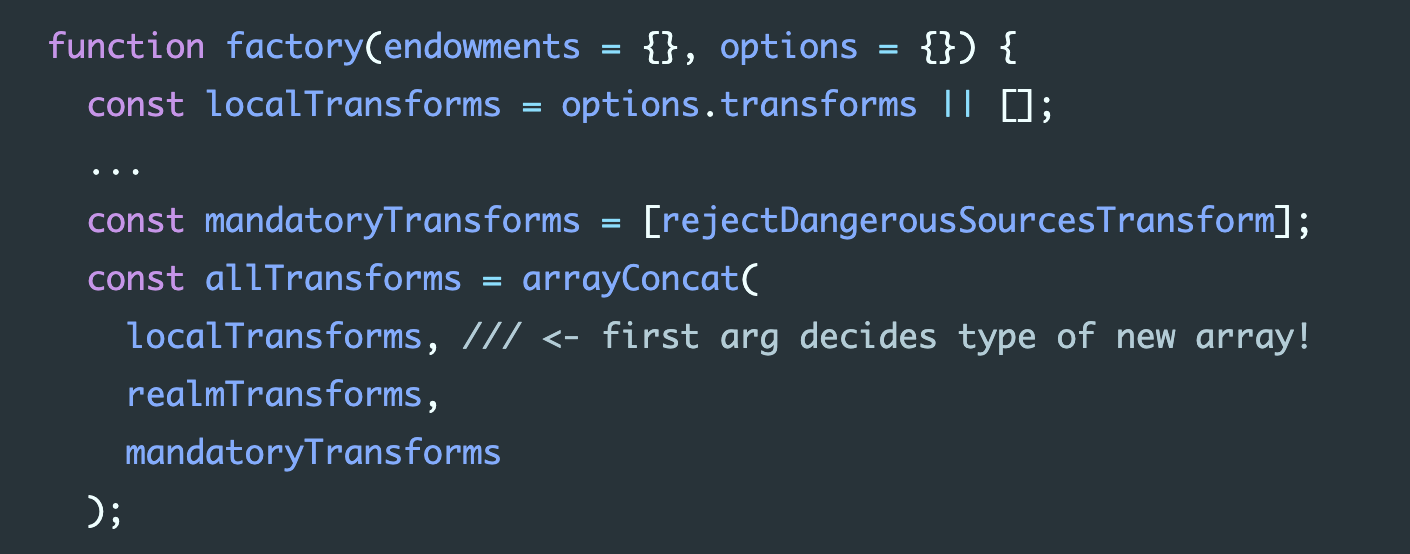

function factory(endowments = {}, options = {}) { const localTransforms = options.transforms || []; ... const mandatoryTransforms = [rejectDangerousSourcesTransform]; const allTransforms = arrayConcat( localTransforms, /// <- first arg decides type of new array! realmTransforms, mandatoryTransforms );

The arrayConcat function is a safely-uncurried version of Array.prototype.concat, so it is not vulnerable to modification by the confined code (aka “prototype poisoning”), and will behave as JavaScript specifies. But the official JavaScript specification has an interesting property: the type of the resulting Array is decided by the .constructor property of the first argument. This behavior makes more sense in the original form (allTransforms = [].concat(localTransforms, realmTransforms, mandatoryTransforms)), but that would be vulnerable to prototype poisoning.

Since the user’s localTransforms appears first, it gets to control the creation of the new Array. This allows the attacker to control the type of allTransforms (and indeed its entire value), so when the second target (applyTransforms) executes the list of transforms by calling transforms.reduce, the attacker has control over reduce():

function applyTransforms(rewriterState, transforms) { ... rewriterState = transforms.reduce( /// <- relies on .reduce of attacker-controlled object (rs, transform) => (transform.rewrite ? transform.rewrite(rs) : rs), rewriterState );

As before, the attack used its reduce() to get access to a primal-realm function object, in this case the arrow function that normally invokes transform.rewrite. From there, it climbs the constructors out to a full-powered eval.

The problem here is that the (defensive) shim is incorrectly relying upon the behavior of the (potentially malicious) caller and the arguments it provides. Our definition of “defensive consistency” is that a piece of code must provide correct service to all correctly-behaved customers, even if other customers do not behave correctly. Allowing one caller to compromise the service does not meet this goal.

Even when a function is documented as accepting an Array argument, we must remember that what it actually receives is merely an alleged Array. In fact, the argument is whatever the caller provided. We can only use instance methods like reduce on that argument if we intended the caller to have access to the parameters we pass into it, and control over the result we get back out, and that is not the case here. We must be defensive against all callers that have access to this function.

The root cause was a combination of two mistakes. applyTransforms is not exposed to untrusted code, so we assumed that it did not need to be defensive against its inputs (it should have been able to rely upon transforms being a real Array). But the surprising behavior of Array.prototype.concat elsewhere in the system (obscured by using the uncurried arrayConcat form) gave the attacker control over one of applyTransforms’s arguments. If applyTransforms had been written defensively against even internal callers, then the concat issue wouldn’t have been a problem.

This highlights the value of POLA (the Principle Of Least Authority), and “defense in depth”. By practicing defensive programming at all levels, even against “friendly” callers, we can limit the reach of bugs, and increase our chances of avoiding an exploitable vulnerability.

We fixed this issue by replacing the transforms.reduce with a different function named arrayReduce that we obtain by uncurrying it from Array.prototype.reduce. As we’ll see later, this fix is insufficient: the real problem is with the concat.

rewriterState = arrayReduce( /// not controlled by attacker transforms, (rs, transform) => (transform.rewrite ? transform.rewrite(rs) : rs), rewriterState );

Uncurrying only gives a reliable result if run before the instance methods may have been corrupted. We need to grab a copy of the original Array.prototype.reduce before the untrusted code ever gets to run, and use that stashed copy later. The attacker’s confined code might replace that property with a fake reduce() function as soon as it gets control. But by that point it’s too late for the attacker. We use this pattern throughout the Realms shim. But the rewrite-transforms code is new, and did not happen to follow this pattern.

Powerful Unfrozen Primordials Considered Harmful

“Primordials” are the core JavaScript objects that must exist before any code runs, like Object, Array, Number, Function, etc, and are used by pretty much every line of JS everywhere. However they are still Objects at heart: they have properties, prototypes, .toString(), and (in a normal environment) they can be modified.

These recent bugs are specific instances which highlight a deeper issue: mutable primordials in general are really hard to secure, and having multiple sets of primordials forces us to keep track of which ones should be accessible to each function. We must prevent untrusted code from reaching any primordial that grants access to platform-level authorities like require().

In its current form, the Realms proposal describes two separate concepts: Realms (aka “Root Realms”), and Compartments (aka non-root realms). Each Root Realm has its own set of primordials, which may or may not be frozen. Each Compartment has a separate global (which also may or may not be frozen, independently of the primordials), and lives inside a specific Root Realm. A single Root Realm can contain an arbitrary number of Compartments.

The Realms proposal, and the realms-shim package, make it possible to create multiple Root Realms. The current SES shim creates a new Root Realm and then freezes all of its primordials. SES leaves the primal realm (mostly) untouched and mutable. As a result, all of its primordials have access to the real Function constructor, and from that you can access the platform global, with all the platform-level authorities like require(), window, and document. This makes the primal-realm primordials very powerful, and they must be protected accordingly.

As we’ve observed, it is very difficult for code in the unfrozen primal realm to safely interact with untrusted code in the frozen SES realm. Every such interaction must carefully guard against leaking a primal-realm object, because every such leak could be used to modify a primordial that some other code depends upon, or to evaluate code against the all-powerful platform global object. This prohibits the use of normal Objects as arguments and return values across this boundary, leaving only primitive data types (basically strings, numbers, and Bool, which are safe, immutable, and not Object). In addition, the defensive code must protect against exceptions that might expose an Error object from the wrong Realm. This leads to a lot of code (and attack surface) for what should otherwise be a very basic interaction.

For the general case, the “Membrane” pattern was designed to provide a place to apply this protection. Membranes are a layer of code on both sides of the boundary, each relying upon the other, that protects non-Membrane code against the far side. A fully general-purpose membrane would convert each non-primitive value that passes the boundary into an equivalent form made up of types from the correct Realm, which behaves just like the original (e.g. Objects would be represented by a Proxy that could react to property assignments by instructing the other side to modify its own properties, etc). Each time a function is invoked across the boundary, the arguments and return values must be wrapped too, and the Membrane must recognize its own proxies so they will round-trip back into the original value. The Membrane must be defined to exclude or alter some sorts of access (i.e. it must not be fully “transparent”), otherwise it would just emulate the dangerous authority that we were trying to withhold. For example, it would have to recognize when Array.prototype was being passed, and prohibit changes that would replace .reduce with a different function. But in other cases, perhaps the defensive code meant to provide a mutable array or object, so the wrapper ought to proxy those mutations too.

It is possible to write a general-purpose Membrane (libraries exist), but at least for the realms-shim, it represents more work (and more code) than seems appropriate, and defining the exact policy that governs the cross-realm interaction takes a lot of care. The membrane could be smaller if it didn’t need to support all possible interactions (e.g. getters and setters, or prototype lookups), but the added complexity of configuring which sorts of interactions are supported might oughtweigh the savings. Of course, the task is made more difficult when one side of the boundary is not frozen, so our membrane code must additionally defend against changes to the primordials it uses to implement the wrappers. It must be evaluated before any untrusted code has a chance to poison the Realm, and it must not depend upon any poisonable primordials.

Consequently most systems, including the realms-shim, implement some ad-hoc subset of a real Membrane, just enough to support the smaller subset of interactions we know it really needs to use. But even a subset must follow the rules above: only passing primitive data, not leaking exceptions, and defending against mutable primordials. Any mistake can result in a confinement breach.

The biggest challenge is that the Realms feature itself is currently implemented by a shim, rather than within the underlying engine. The realms-shim code itself must follow these strict rules too, and each time it failed to do so, we suffered a confinement breach.

When the Realms proposal gets far enough along the standards track to be implemented directly in JavaScript engines (like XS, SpiderMonkey, and V8), we won’t need a shim, and the engine will take responsibility for implementing confinement correctly. This should be a lot easier to get right, because the engine has far more information to work with (and is usually implemented in something other than normal JavaScript, making it harder to accidentally rely upon the behavior of objects coming from the confined code).

In the meantime, we can reduce the attack surface considerably by making sure that all the primordials are frozen, and by having only one set of primordials to think about.

Single-Realm For The Win

We’ve discussed our needs with our partners (incuding Salesforce, MetaMask, Figma, and others who participate in the SES working group), and we’ve determined that most of our collective use cases would be satisfied by a simpler mechanism. We do not really need multiple Root Realms, nor do we need shared mutable primordials. Each compartment has its own mutable global object, its own indirect eval function (and Function constructor) which reference that global, and whatever powers were granted by the compartment’s container. But these are not shared between compartments.

Thus, a safer alternative is to secure a single primal-realm in-place (hiding its original platform global), and to freeze its shared primordials. Rather than trying to defend a vulnerable unfrozen primal realm against outsiders, we make the entire world safe, and remove the distinction between realms.

Code in this one root-realm can then create new Compartments and evaluate untrusted code within those, where they can’t reach the original platform global (with its platform authorities). The confined code can reach the shared primordials, such as Object, Array, Array,prototype, Array.prototype.reduce. But it can’t do anything to them, because they’ve all been frozen already, and it can’t do anything surprising with them, because their constructors don’t lead to a powerful Function object.

This approach requires a different way of setting up the application. If you need to change the platform in any way (e.g. adding a new feature into a standard object on an older platform), that must be done by executing a “vetted shim” to modify the shared primordials right at startup, before the world is frozen. We call these “vetted shims” because we enable them to corrupt the shared primordials, and rely on them not to. For example, our eventual-send shim modifies the Promise object to add methods that implement the eventual-send proposal, so we must run this shim early, before Promise is frozen. But we don’t want the confined code to be able to modify Array to change the behavior of reduce, and it can’t, because we only run it after Array is frozen.

Only after the shared primordials are frozen do we load untrusted code into compartments within that root realm. The result is much safer, and mutually-suspicious code can safely interact with defensive objects that inherit from frozen prototypes, rather than capturing uncurried functions at initialization.

We’re working on a new library, named the evaluator-shim, which implements just the core of the evaluator (the “magic 8 lines of code”, and the parts that surround it). When used in a frozen environment, such as SES, this should provide a significantly smaller security kernel.

Defensive code in this environment still needs to follow several rules to protect itself against possibly-malicious callers and callees, but there are far fewer of them, and they are much easier to follow. The relaxed rules also enable richer interaction like object-based arguments and callbacks. They include things like:

Freeze all outbound objects (with

harden()) before passing them to a caller, who might try to modify them. The primordials are frozen automatically, but all other objects must be frozen explicitly.

Do not rely upon the purported types of inbound arguments, nor the methods which those types ought to provide. Standard types like

Arraycan be converted into reliable forms with e.g.

const realArray = Array.from(allegedArray)or

[...allegedArray], at which point it

is

safe to use their methods like

.reduce.

In this world, functions can freely pass objects back and forth with untrusted code, without worrying about what surprising authority might be leaked by the types of those objects.

Further Bugs Rendered Moot

Shortly after the 1.2.1 release, and before we were able to publish this blog post explaining our plans to switch to evaluator-shim, XmiliaH reported additional breaches in the realms-shim. These are not yet fixed: we discuss these here because we are ending security fixes for the realms-shim, and because they emphasize the value of switching to immutable primordials.

When A String Isn’t Really A String

The first additional attack exploits the fact that one of the subsequent transforms assumes the input argument is a String, and applies a regular expression on it by invoking it’s .search() method:

const htmlCommentPattern = new RegExp(`(?:${'<'}!--|--${'>'})`); function rejectHtmlComments(s) { /// <- s might not be a string! const index = s.search(htmlCommentPattern); if (index !== -1) { throw new SyntaxError(`possible html comment syntax rejected`); } }

This is another instance of not being sufficiently defensive against the input arguments. Some languages submit a string to a regular expression, but JavaScript also does it the other way around: it submits the regular expression to the string. By providing one transform that “converts” the code into a non-string, the confined attacker’s non-string can capture the regexp used by a later transform. In this case, that regexp was a primal-realm object, which the exploit code can again leverage to get to the full-powered Function object.

It would have been a good idea to use uncurryThis to extract a safe uncompromised copy of String.prototype.search ahead of time, and invoking that against the (attacker-provided) alleged string. However the behavior of String and RegExp is complicated enough that this is no sure defense. The safest protection would be to coerce the alleged string into a real string first:

const index = `${s}`.search(htmlCommentPattern);

In fact, defense-in-depth says we should enforce our String expectations independently at all levels. rejectHtmlComments() is responsible for protecting itself, but applyTransforms should also guard against each rewriter function returning a non-String, by coercing the return value of the rewriter immediately after execution. Some of these rewriters are provided by the user, some are local (including rejectHtmlComments), but all should be subjected to the same requirements.

Defensive Consistency

This bug was born in an assumption that rejectHtmlComments could only be called by “trusted” callers, one which was violated by subsequent code refactorings. In the absence of any documentation to the contrary, we should write our code to the discipline of defensive consistency, where the callee must defensively assume that its callers are fallible (buggy or malicious). On entry to the function, the arguments are whatever the fallible caller provided. In the code

function rejectHtmlComments(s) { const index = s.search(htmlCommentPattern);

the callee is invoking an instance method on the argument. Therefore the response is only according to that argument, whatever it is. rejectHtmlComments is also giving that s argument access to the htmlCommentPattern object. Depending on the callee’s purpose, both of these assumptions may be appropriate.

When the callee’s correctness depends on stronger assumption, such as the s argument being a string, it must either:

check or coerce the argument before using it, or

document that this function is

not

defensively consistent, must only be called from code that upholds its preconditions, and must not be allowed to leak or escape (and thus become accessible to code that doesn’t follow these rules).

Array Concatenation Part Deux

XmiliaH’s second additional attack targets the “fixed” 1.2.1 code. We had misunderstood the significance of how Array.prototype.concat gives the first argument control over the result, and only addressed one symptom (control over reduce giving the attacker access to a Function object). This new attack used a second symptom: access to the primal-realm Array object, which is just as bad. The attack creates an Array subclass whose constructor grabs a copy of its superclass:

let LastBadArray; class BadArray extends Array { constructor() { super(); LastBadArray = this; } } Realm.makeCompartment().evaluate('', undefined, {transforms: new BadArray()}); const HostObject = LastBadArray[0].__proto__.constructor

Uncurry Once, Early

In addition, during internal post-release review, we identified a third problem. The cross-Realm object leakage was fixed by evaluating the applyTransforms() function (as a string) inside the target Realm, each time a new evaluation occurs. The fake reduce() problem was fixed by having applyTransforms extract and stash the Array.prototype.reduce function before the attacker-supplied transform functions were executed:

export function applyTransforms(rewriterState, transforms) { const { create, getOwnPropertyDescriptors } = Object; const { apply } = Reflect; const uncurryThis = fn => (thisArg, ...args) => apply(fn, thisArg, args); const arrayReduce = uncurryThis(Array.prototype.reduce); /// <- extracted multiple times! ...

But doing both means that the function is extracted every time the evaluator is invoked, which means the attacker could perform multiple evaluations in a child Realm: first to modify Array.prototype.reduce, second to access the parent Realm’s Function object.

None of these bugs would be an issue if we were using the evaluator-shim in a single-frozen-Realm environment. The Array and RegExp objects would already be available to the attacking code, along with the Function constructor those can reach. That Function constructor would be tamed to not provide access to the all-powerful platform global object. To be precise:

Inside each Compartment, the global object has a

Functionconstructor, which builds functions that use a per-Compartment global.

The

Functionconstructor reachable through the prototype chain of

all

other primordials will throw an exception, rather than reveal the platform global object.

The arrayConcat attack is particularly interesting. In the exploit, the goal was to get access to any primal-realm object. If we had a single-frozen-Realm environment, that wouldn’t have been useful. However by controlling concat, the attacker code also gets to control the return value of concat(). They already control the first input to concat() (the “local transformations”), but there are subsequent mandatory transformations which they could choose to omit. We use those transformations to implement the regular-expression check that rejects potential HTML comments, as well as other dangerous source constructs like dynamic import expressions. By changing the allTransforms array, the attacker could bypass those checks and breach the sandbox through other pathways.

One fix would be to supply a real Array as the first argument of the uncurried arrayConcat function, since only the first input to concat() is treated specially:

const allTransforms = arrayConcat( [], localTransforms, realmTransforms, mandatoryTransforms );

However the most obviously-correct fix is to use JavaScript’s “spread operator” (...) to combine the arrays, which doesn’t treat its first input in the same special way that Array.prototype.concat does:

const allTransforms = [ ...localTransforms, ...realmTransforms, ...mandatoryTransforms ];

The evolution of this code is educational: originally, the rejectDangerousSources test was done with a distinct call, and would have been applied regardless of whatever tragic misfortune might have befallen allTransforms. When the new “generic source transforms” feature was added, it was natural to refactor the code to apply this check as just another transform, and indeed that change used the ... spread operator as described above. However, in fixing the previous batch of confinement bugs, the assembly of allTransforms was changed to use an uncurried arrayConcat out of concern that the ... approach could somehow be tricked by a poisoned prototype.

The two changes (refactoring rejectDangerousSources into a transform, and combining the transforms with arrayConcat) were safe individually, but when they met, they accidentally synthesized an ability to disable important safety checks.

Lessons and Plans: Moving to evaluator-shim

Looking back at the last several security bugs, we can distinguish between those which exploited mutable primordials, those which exploited cross-root-realm isolation bugs, and those which would not have enabled a breach in a single isolated frozen root-realm:

Bug | Safe in single frozen root-realm ? |

|---|---|

no | |

safe: the Error object is powerless and frozen | |

safe: Function object is tamed | |

safe:

is frozen | |

safe: the record is an Object of the same safe Realm | |

safe: Function is tamed | |

no | |

safe: RegExp is powerless | |

safe:

is powerless | |

localTransforms uses concat to control allTransforms | no: can bypass mandatoryTransforms |

multiple uncurryThis in applyTransforms allows poisoning of

| safe:

is frozen |

The majority of these bugs would not have enabled a confinement branch if the environment was frozen and there was only one root-realm.

As a result, and after considerable discussion with our partners, we are shifting our security focus away from realms-shim and towards the new evaluator-shim library. For new JavaScript features, shims are primarily constructed to help potential users learn about the feature, to provide invaluable feedback during the standardization process. Sometimes they are used to inject the new feature into older environments, but they are rarely expected to defend against malicious behavior. Few shims are designed to be as secure as the feature they represent, and we’ve found the realms-shim is difficult to implement securely without engine-level support, especially in the face of mutable primordials and multiple root realms. We think it can be done, but it would take more time and effort than is warranted, given the smaller codebase and attack surface offered by the single-frozen-realm evaluator-shim approach.

Starting now, we are no longer committed to maintaining the realms-shim — either its functionality or its security. The realms-shim/SECURITY.md will be updated to reflect the change, instructing bug submitters to file the bugs publically, and any realms-specific security bugs reported to security (@agoric.com) will be re-filed as public GitHub issues (if you aren’t sure, of course, submit it to security@ and we’ll figure out whether to publish it or not).

We will move SES onto the evaluator-shim, and will change its API to reflect the “secure-in-place” approach.

We do intend to make SES and the evaluator-shim secure, but neither has been through a proper review and audit process yet. Once we announce each is ready, we will switch to the usual responsible-disclosure process for any security-sensitive bugs in evaluator-shim or SES: these should be reported privately via email or Keybase, and we’ll coordinate a timely fix and disclosure with users of the libraries. As always, check the SECURITY.md documentation for instructions on bug submission.

Frozen primordials are a good start, but we also need to build a checklist of defensive-programming guidelines. We can further support programmers by encoding these guidelines into IDE plugins, linters, documentation conventions, and static type annotations. When looking at any function, it should be clear what that code relies upon, and what it is prepared to defend against, and it should be difficult to make the transition from “only called by our own code” to “might be called by someone else” without being forced to look at the documentation and add the necessary safety checks.

Security is a process, and requires careful balance between risk and features. We believe a smaller kernel is the right approach, and look forward to improving our codebase further.

Timeline

04-Oct-2019 (Fri)

1:07am PDT: XmiliaH submits email about Edge

Symbol.unscopablesbreach

12:27pm PDT: GitHub advisory GHSA-wppv-m27m-jrf7 opened

12:30pm PDT: Agoric engineer JF Paradis confirms bug

07-Oct-2019 (Mon)

5:00pm PDT: XmiliaH submits email about rewrite-transformer breach

5:44pm PDT: GitHub advisory

opened

08-Oct-2019 (Tue)

3:47am PDT: XmiliaH submits additional breach: subclassing

Arraywith overridden

reducemethod

09-Oct-2019 (Wed)

14:46pm PDT: Edge fix lands as part of larger refactoring

16-Oct-2019 (Wed)

Microsoft Security Respose Center notified about Edge bug, Case#54433

11:42am PDT:

released

12:07pm PDT:

released

12:14pm PDT:

published

NPM advisory submitted

17-Oct-2019 (Thu)

2:22am PDT: XmiliaH submits

BadArrayand

RegExpbreaches

10:50am PDT: NPM advisory [1218](https://www.npmjs.com/advisories/1218] published

18-Oct-2019 (Fri)

MSRC confirms reproduction, declines to classify as security sensitive, approves disclosure

GHSA-wppv-m27m-jrf7 published

24-Oct-2019 (Thu)

blog post published

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Mark Miller and JF Paradis for feedback and wordsmithing, XmiliaH for their enthusiastic and conscientious disclosure of bugs in the realms-shim, and to the NPM and GitHub security teams for help with the advisories. We are grateful for their time and energy.